Summary

As the last US military aircraft depart Kabul, so closes a chapter of U.S. involvement in the country. Will it also end a period of growth of the domestic internet in Afghanistan?

As the last U.S. military aircraft departed Kabul, so closed a chapter of U.S. involvement in the country. Will it also end a period of development of the domestic internet in Afghanistan?

Growth of Afghan domestic internet

In 2012, my former colleague and Renesys co-founder Jim Cowie wrote a blog post, “Could It Happen In Your Country?”. Inspired by our coverage of the internet shutdowns of the Arab Spring the previous year, Jim attempted to do a back-of-the-envelope analysis that would gauge how easily a country-level shutdown could occur based on the number of unique international links that connected a country to the internet. The supposition being that more international links makes a country more “resistant” to a complete disconnection.

In the analysis, the United States and most of Europe were rated as resistant, while countries with a single state telecom controlling international connectivity, like Cuba, North Korea and Syria, were rated as “severe risk.” Perhaps one of the more counter-intuitive ratings from that analysis was Afghanistan’s classification as “low risk.” The fragmented nature of the country’s internet, driven by its austere mountainous geography, meant that shutting down service in Afghanistan would require more than a single kill switch.

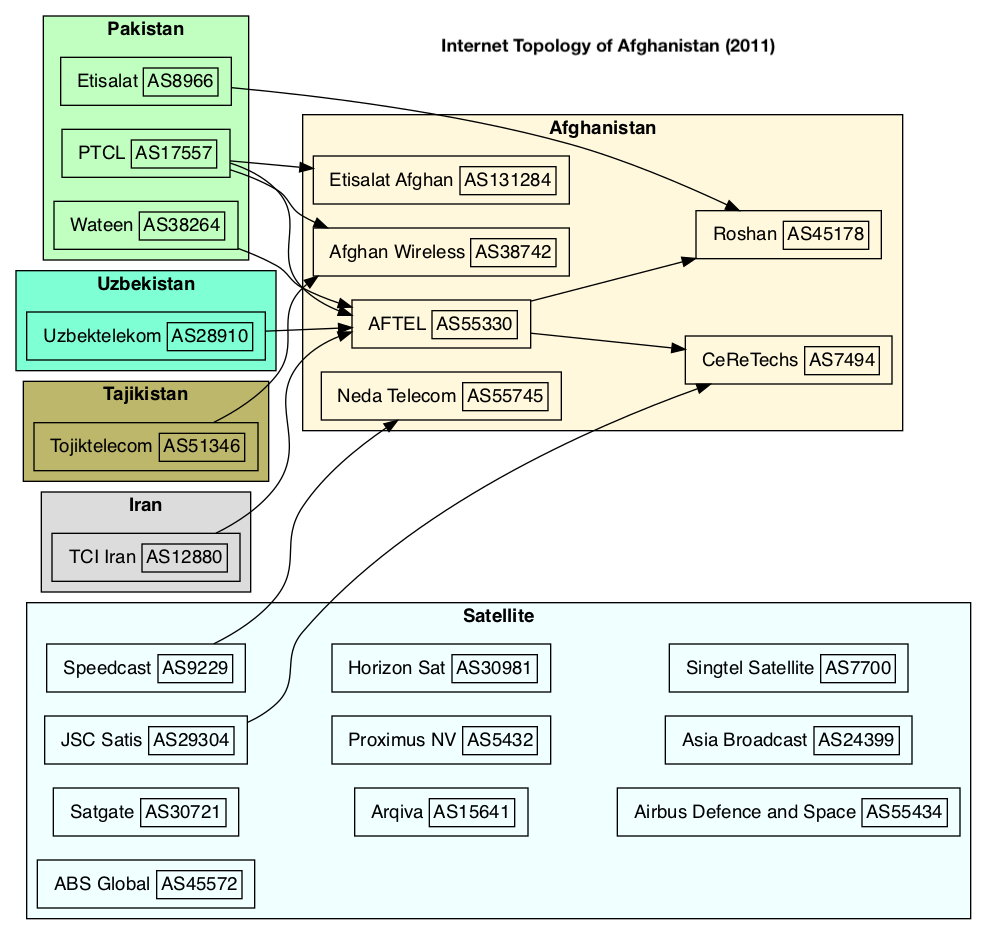

The diagram below illustrates the topology of the internet of Afghanistan based on BGP data from 10 years ago. Six ASNs represented its domestic internet with international bandwidth coming from either satellite providers or its neighboring countries, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Iran. Service from the latter two countries began in the spring of 2010. (Note the satellite providers shown without arrows originated IP space geolocated to Afghanistan.)

The geographic diversity of Afghanistan’s international gateways was born of necessity. Provincial population centers often had closer ties with neighboring countries than with the nation’s capital. For example, Herat in western Afghanistan receives services such as electricity and internet service from neighboring Iran.

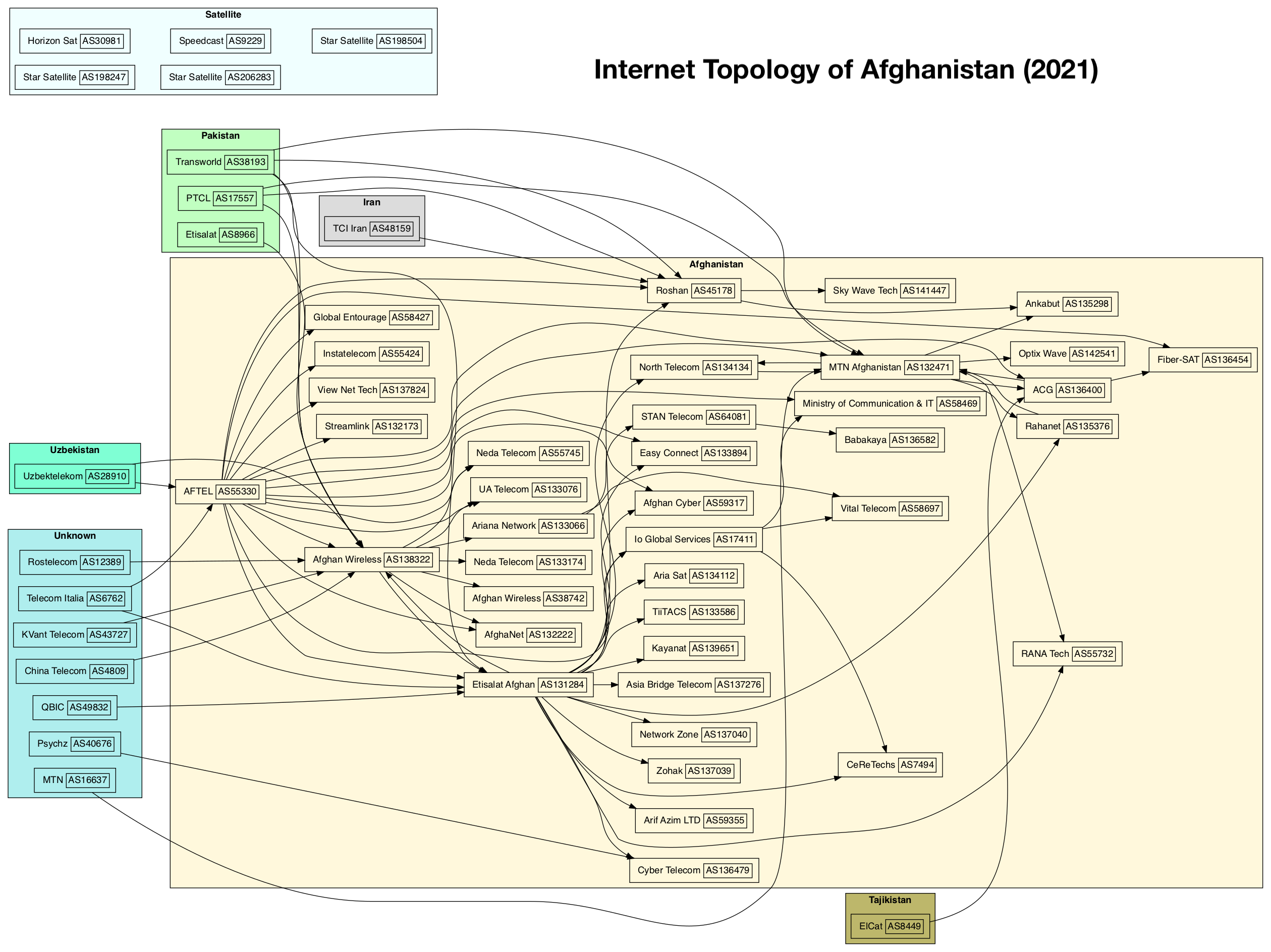

Fast forward 10 years and note the internet in Afghanistan has grown substantially - from six domestic ASNs to 40! AFTEL (AS55330) still gets connectivity from neighboring countries and still serves a central role operating the country’s fiber backbone, such that it is. Most Afghans access the internet through mobile handsets using wireless carriers such as MTN Afghanistan (AS132471), Etisalat Afghanistan (AS131284), Afghan Wireless (AS38742) and Roshan (AS45178).

In the above diagram, international providers without a clear country geographic route are grouped in a cluster called “Unknown.” Despite this uncertainty, Rostelecom of Russia and China Telecom very likely provide service via northern routes while many others likely provide service via Pakistan.

Risks of disruption

Despite recent events in Afghanistan, we have yet to see any national internet disruption. However, the risks to the country’s domestic internet sector remain stark. One of the catalysts of Afghanistan internet growth has been the development of a fiber optic backbone depicted in the diagram below from a UNESCAP presentation from 2015. This fiber backbone is a vulnerable piece of physical infrastructure that would be difficult to repair if it were damaged due to sabotage or a natural event.

Another risk comes from the state of Afghanistan’s crumbling economy. New international restrictions on the ability of the country’s new government to move money in and out of the country will hamper its ability to pay for international bandwidth, source replacement parts or hire technical specialists to maintain all the moving parts of a national internet. However, Syria’s state telecom has been the subject of sanctions for years but has managed to keep its services running.

MTN had already said last year that they were planning to depart Afghanistan (along with the markets of Iran and Yemen) to focus on their business in Africa. It would not be surprising to see one or more foreign operators make the business decision to cease operations—a shutdown based on simple economics.

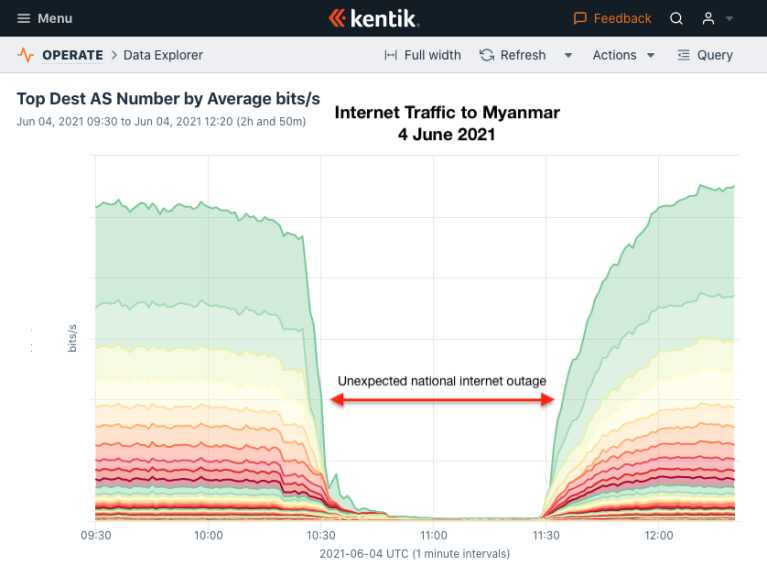

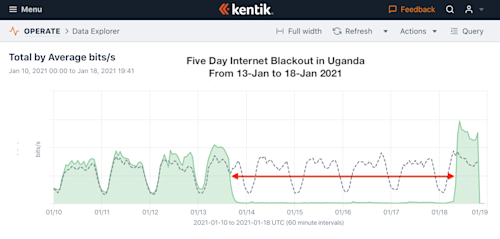

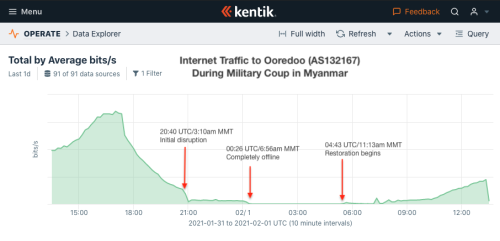

Finally, the threat of censorship and communications blackout are a very real possibility given the track record of the new Afghan government. As we saw in the case of Myanmar earlier this year, government shutdowns don’t require a centralized kill switch, despite a “low risk” rating from Jim’s 2011 analysis.

Conclusion

The internet of Afghanistan is in a precarious state with the growth of the past decade at risk. Could the alignment of Pakistan’s Prime Minister Imran Khan and the new Afghan government herald a greater role for Pakistan in connecting Afghanistan? Or will we watch a slow decline of internet service marked by shutdowns and increased censorship? We will be watching the situation closely.

In Memoriam: Marc Lipton

Marc was one of the people I used to turn to when trying to understand the telecom sectors of Iraq and Afghanistan. After working 30 years as a lawyer for AT&T handling regulatory issues, Marc retired and took a job advising the government of Iraq on building the legal structure to foster a healthy telecom sector. After several years there, he moved on to work in a similar role for the government of Afghanistan.

While working in Afghanistan, his hotel in Kabul had been bombed - thankfully he was away at the time. I told him that I hoped he was paid well for the risks he was taking. He replied that actually he wasn’t paid much. “Why do it then?,” I asked. He replied that he wanted to make things better in Afghanistan so that his grandchildren didn’t end up getting sent to fight there.

Marc died of a heart attack in 2018 at age 66. Rest in peace, Marc.