Summary

In this post, Doug Madory digs into the latest submarine cable failure impacting internet connectivity in Africa: the Seacom and EASSy cables suffered breaks on May 12 near the cable landing station in Maputo, Mozambique.

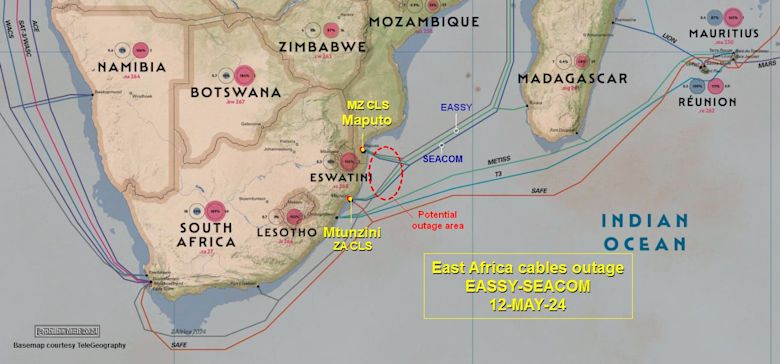

On Sunday, May 12, two submarine cables (Seacom and EASSy) suffered breaks along a stretch of coastline between the cable landing stations in Mtunzini, South Africa and Maputo, Mozambique. It was the latest in a historically bad run of submarine cable failures that have led to disruptions of internet service around the continent of Africa.

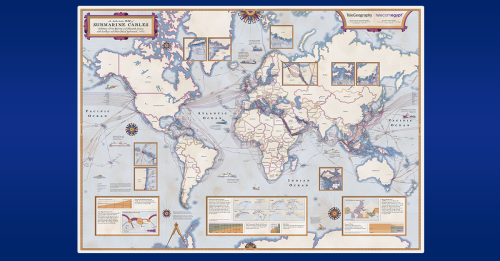

“Keen observer of the submarine cable industry” and friend of the blog, Philippe Devaux, created this markup of a Telegeography map depicting the location of the cable cuts.

Impacts were observed from Kenya down the east coast of Africa to South Africa beginning just before 07:30 UTC (10:30 am East Africa time). Among the East African countries impacted, Tanzania experienced the most severe disruption, according to Kentik’s aggregate NetFlow. This observation was corroborated by outside sources such as the Internet Outage Detection and Analysis project at Georgia Tech and Cloudflare’s Radar.

We’ll get into more detail below, but let’s first review some history.

A rough few months

If we start the timeline of this run of misfortune last summer, we can include the undersea landslide in the Congo Canyon last August that took out multiple cables along the West Coast of Africa. In a blog post, I detailed the impacts and discussed the history of threats to submarine cables from natural threats such as earthquakes.

In February, multiple submarine cables connecting Europe and Asia were cut in an incident in the Red Sea on February 24. Having been attacked by Houthis from Yemen, the MV Rubymar was abandoned and left to drift at sea. Ultimately, its anchor snagged and cut three cables in the sea inlet’s shallow waters. I published my analysis as part of an investigation led by WIRED magazine to dig into the incident.

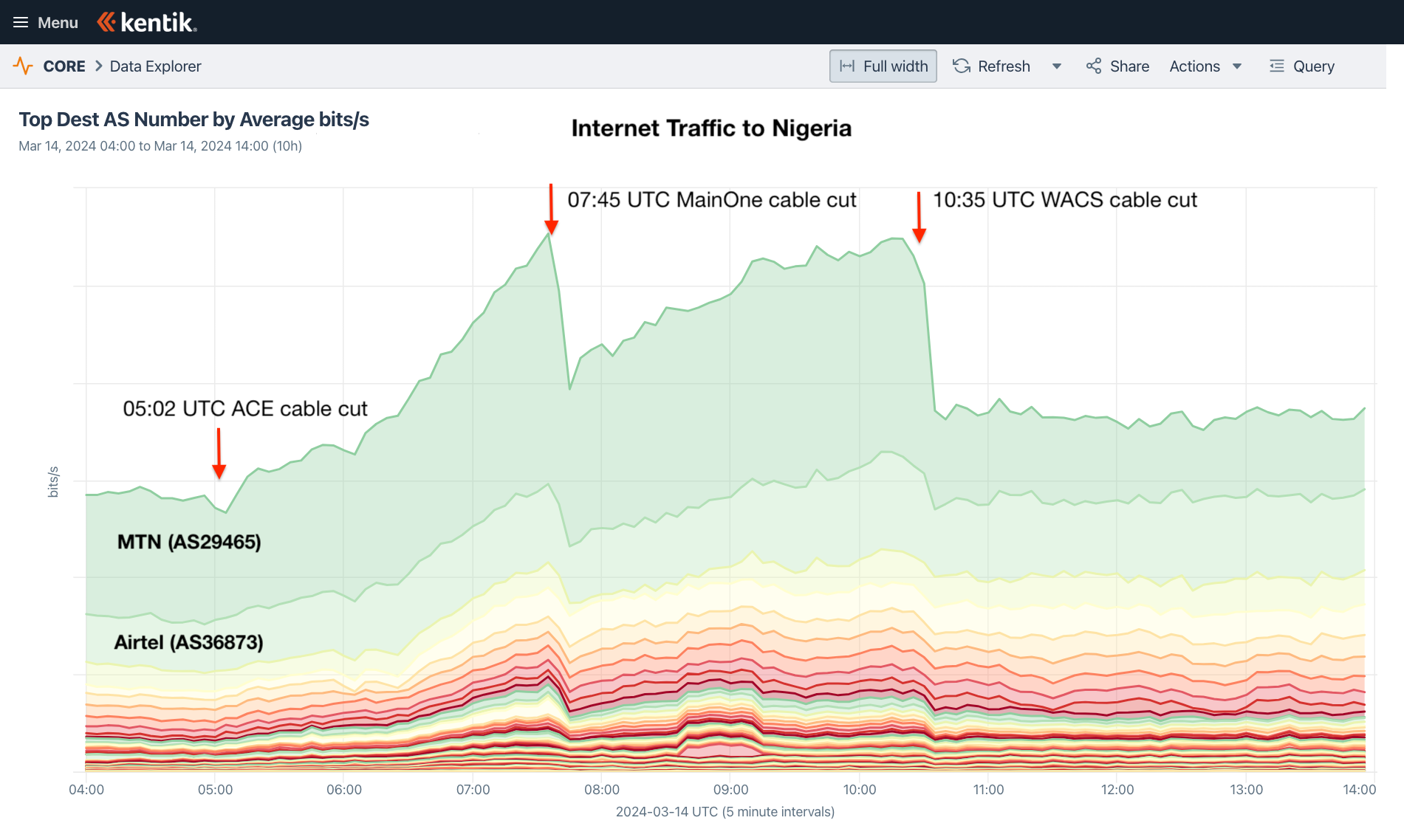

Finally on March 14, four submarine cables (ACE, MainOne, WACS, and SAT-3) suffered failures off the coast of Côte d’Ivoire over a period of 5.5 hours. The suspected cause was an undersea landslide in the Trou sans Fond (“bottomless pit”) in an undersea canyon running from the coast. The last of the repairs was finally completed on May 10.

Digging into the impacts

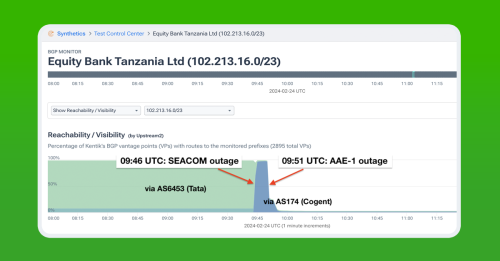

Vodacom Tanzania was one of the most impacted providers in East Africa. On May 15, they announced a full restoration of services, but BGP data reveals the scramble to re-establish connectivity immediately following the loss of the submarine cables on the 12th.

While some Vodacom Tanzania routes were simply withdrawn at the time of the cable outages, others, such as 197.250.0.0/18 depicted below, were rerouted over Tigo (AS37035) in an attempt to attain transit from Djibouti Telecom to the north. Vodacom Tanzania (AS36908) was primarily using Seacom’s IP transit service (AS37100), which relies on its eponymous subsea cable, as well as transit from the parent company’s network in South Africa (AS36994).

Eventually, Tanzanian providers were able to reroute traffic over alternative cables until the cable repairs take place.

Conversely, Safaricom of Kenya was largely able to weather the loss of the cables by reverting to other sources of transit.

An effective BGP configuration is pivotal to controlling your organization’s destiny on the internet. Learn the basics and evolution of BGP.

The BGP analysis shows instability of WIOCC transit beginning around 07:28 UTC on May 12, until its complete loss over an hour later. From a BGP perspective, the loss was replaced by transit from China Telecom Global (AS23764), as depicted in this BGP visualization of a Safaricom route.

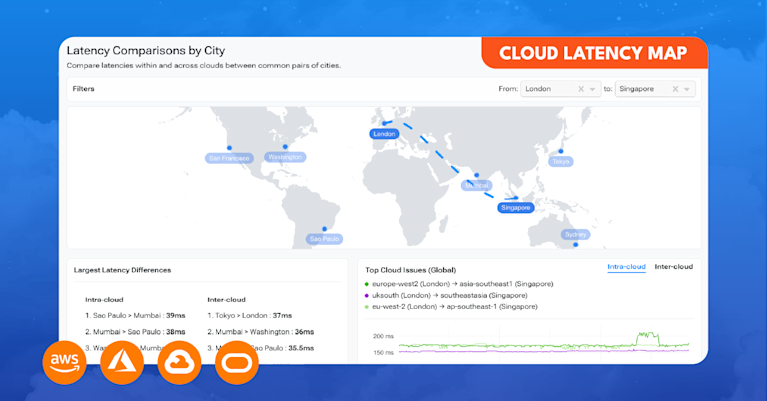

Impacts on cloud connectivity

As with previous submarine cable disruptions, the latest cable cuts affected connectivity between public cloud regions. Kentik’s multi-cloud performance capability, which we use as the basis of the Cloud Observer blog series, captured the impact.

The most visible impact, illustrated in the screen captures below, were measurements between cloud regions in South Africa and Asia. Latencies were observed to increase dramatically as traffic was redirected along longer geographic paths due to the loss of these cables.

In the first graphic, measurements from Azure’s region in Johannesburg, South Africa southafricanorth to Google Cloud’s asia-south1 region in Mumbai, India, jumped by 74 ms.

In the graphic below, AWS’s region in Cape Town, South Africa af-south-1 experienced an increase of over 120 ms to Google Cloud’s asia-southeast1 region in Singapore.

These examples once again prove that the cloud providers must rely on the same submarine cable infrastructure as everyone else and can be impacted by cable cuts in similar manners.

Conclusions

In the past decade, the number of submarine cables serving the continent of Africa has nearly doubled, leading many internet infrastructure observers, such as yours truly, to believe that this abundance of cables contributed to a greater degree of resilience.

However, in the past nine months, Africa has endured four separate cable incidents, each resulting in the failures of multiple submarine cables. This leads to some tough questions. Are environmental conditions contributing to greater underwater turbidity that could lead to more undersea landslides? Has increased commerce led to greater maritime traffic and, thus, a greater threat from ship anchors?

We have done a lot in the past decade to keep local internet traffic local by encouraging domestic interconnectivity through internet exchanges, for example. For the primary hubs of Africa (Nigeria, South Africa and Kenya), the amount of content that is served through local caches is enormous compared to where we were a decade ago, but it doesn’t appear to be enough. We still have a high degree of internet connectivity dependent on submarine cables despite the fact that much (most?) content now gets served locally in many of these markets.

We’ll need to learn what was the cause of this latest incident. While we are waiting, it is worth considering that WIOCC’s EASSy cable and the Seacom cable failed within minutes of each other — similar to the cable cuts in the Red Sea, which were caused by a ship anchor. The cable failures caused by undersea landslides (Congo Canyon and the Côte d’Ivoire’s Trou sans Fond) were spread out over multiple hours.

According to a recent LinkedIn post from Devaux, the cable repair ship Leon Thevenin has been dispatched from Cape Town, South Africa, to make the necessary repairs.

Hopefully these are the last submarine cable breaks to disrupt African connectivity for a very long time.

For additional discussion on the topic of the recent spate of submarine cable cuts affecting internet connectivity in Africa, tune into a recent episode of Kentik’s Telemetry Now podcast hosted by my colleague Phil Gervasi.