Outage in Egypt impacted AWS, GCP and Azure interregional connectivity

Summary

On Tuesday, June 7, internet users in numerous countries from East Africa to the Middle East to South Asia experienced an hours-long degradation in service due to an outage at one of the internet’s most critical chokepoints: Egypt. In this blog post, we review some of the impacts as well as compare how this disruption affected connectivity within the three major public cloud providers.

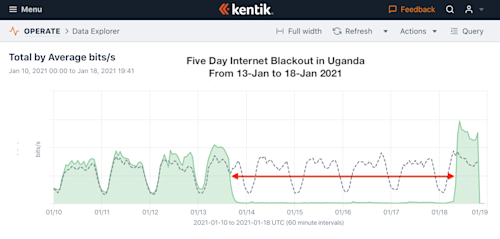

On Tuesday, June 7, internet users in numerous countries from East Africa to the Middle East to South Asia experienced an hours-long degradation in service due to an outage at one of the internet’s most critical chokepoints: Egypt. Beginning at approximately 12:25 UTC, multiple submarine cables connecting Europe and Asia experienced outages lasting over four hours.

As I show below, the impacts were visible in various types of internet measurement data to the affected countries. In addition, the impacts were visible in Kentik’s synthetic measurements between the regions of the three major public cloud providers: AWS, GCP and Azure underscoring that even the cloud must rely on the same submarine cable infrastructure that the rest of us do.

TransEgypt

Egypt’s Suez Canal is a vital waypoint in the world of international shipping. The canal’s role as a global maritime chokepoint was underscored last year when the massive cargo ship Ever Given became stuck in the canal. In the six days it took to free the Ever Given, hundreds of other ships were delayed in making their deliveries, temporarily halting a large portion of global trade.

Perhaps less appreciated is the fact that Egypt also serves as a critical internet chokepoint. Virtually all internet traffic between Europe and Asia rides along submarine cables which run through this country.

Of course, the submarine cables traversing Egypt aren’t laid in the canal itself. Instead they come ashore at Abu Talat and Alexandria on the Mediterranean, travel overland to the Red Sea where they are deposited back in the water at cable landing stations such as Zafarna. Telecom Egypt operates this overland passage called TransEgypt and collects a hefty payment from each submarine cable using the route. For those circuits that don’t travel over the Egyptian desert, the Suez Canal Authority offers fiber optic lines run in ductwork encased in concrete on the side of the canal.

According to Telecom Egypt, TransEgypt operates as a mesh, meaning that it should be able to survive the failure of any particular segment. Despite this assurance, there have been a handful of brief outages in this overland route through the years. When these outages occur, they can impact millions of people in dozens of countries.

In February 2013, multiple submarine cables traversing Egypt experienced outages lasting several hours due to a fire set by thieves in a supremely misguided attempt to extract copper from the fiber optic cables. In March 2013, the Egyptian Navy arrested divers off the coast of Alexandria who had damaged SeaMeWe-4 when they detonated underwater explosives purportedly to collect scrap metal. (Note: the TransEgypt circuits were unaffected by the government-directed internet shutdown in January 2011).

Thankfully last week’s outage occurred on land and could be quickly repaired. The alternative would have been a nightmare scenario. The SeaMeWe-4 cut in March 2013 led to severe connectivity problems in numerous countries, lasting weeks in many cases.

Egypt’s status as a global internet chokepoint is a perennial topic at nearly every submarine cable conference and there have been several attempts to establish routes around Egypt and the Suez. The JADI system was one such route. Its name came from the cities which constituted its path: Jeddah, Amman, Damascus and Istanbul. Unfortunately, the complete circuit was short-lived. Months after its activation, Syria descended into civil war. The fighting severed the link which was never reconstituted.

Additionally, EPEG (Europe-Persia Express Gateway) is a terrestrial circuit running from Frankfurt, Germany to Iran and Oman in the Persian Gulf. It was activated in April 2013 months ahead of schedule to supply bandwidth to the Middle East reeling from the loss of SeaMeWe-4 the previous month. Due to a variety of factors, EPEG never altered the region’s dependence on Egypt-based routes and most recently, the circuit was severed in March due to the on-going fighting in Ukraine.

Various country-level impacts

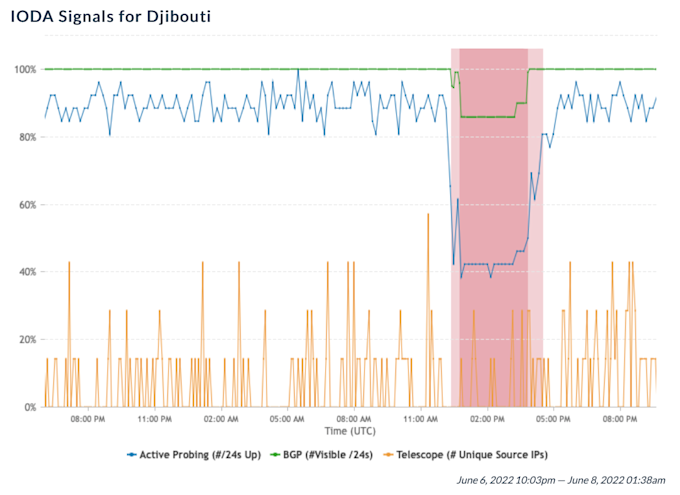

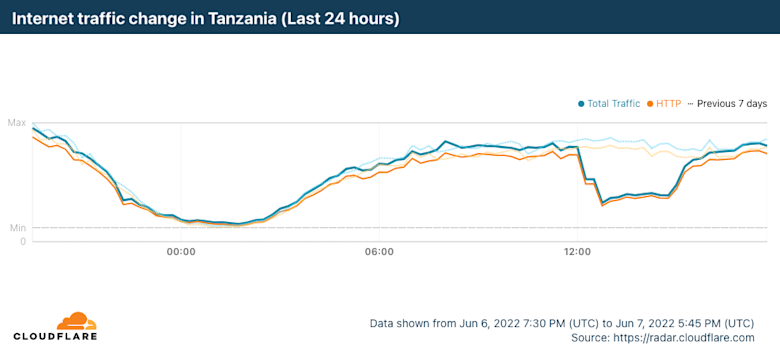

The Internet Outage Detection and Analysis (IODA) project at Georgia Tech published charts showing impacts to Somalia, Tanzania, Djibouti and Ethiopia in East Africa.

Cloudflare Radar published a blog post including the one of Tanzania below showing the impact to their traffic resulting from the outage.

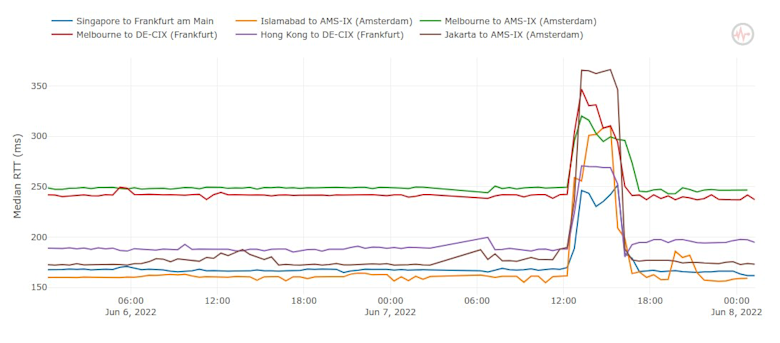

And finally, Romain Fontugne of the IIJ Research Lab in Japan contributed the view below based on RIPE Atlas probe measurements between Europe and Asia. According to these measurements, latencies from one region to the other experienced dramatic increases until the Egypt circuits were restored.

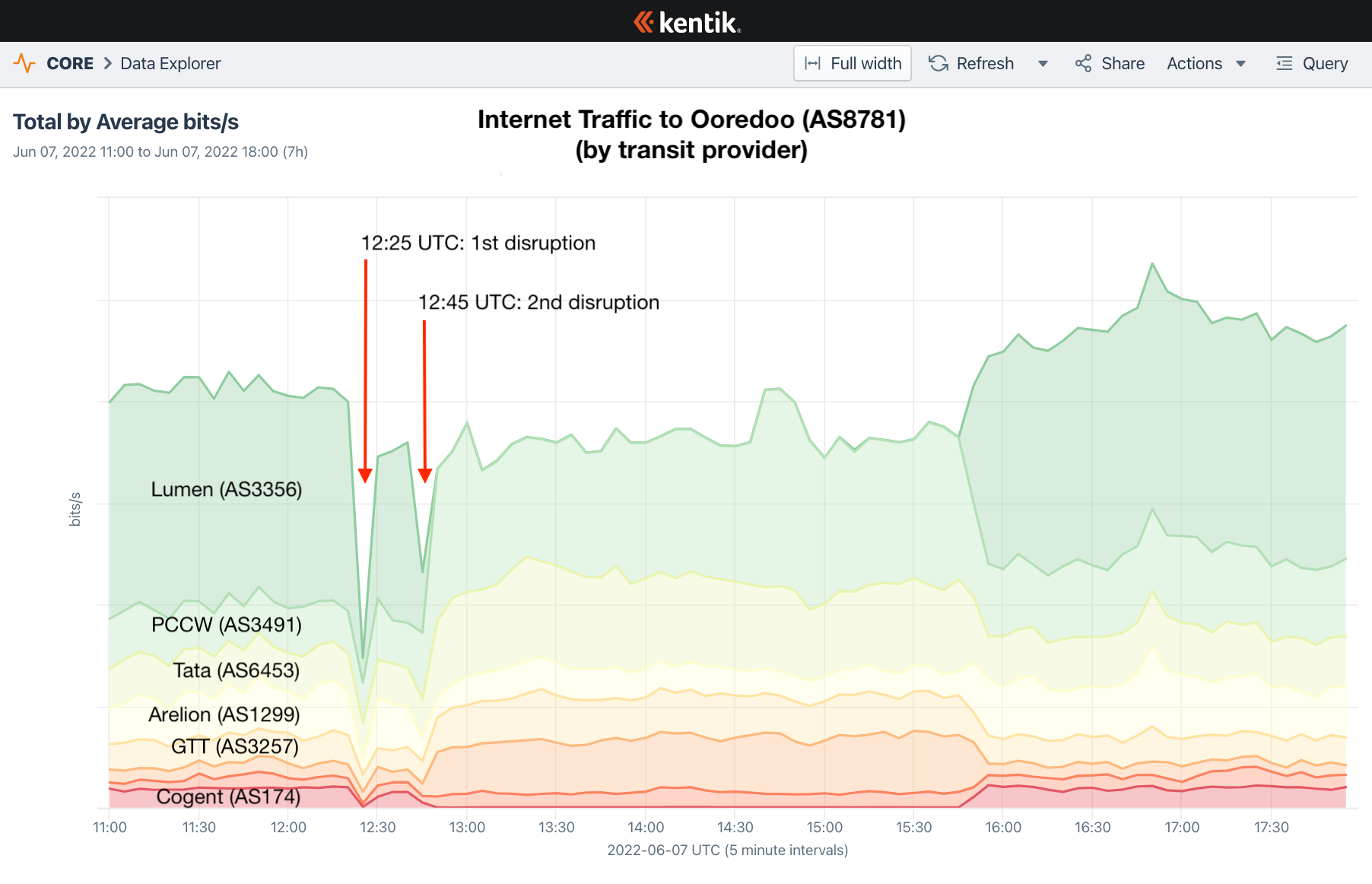

When we look at the traffic impacts through Kentik’s aggregate NetFlow data, we can see network service providers in various countries shifting transit to recover from the loss of connections disrupted due to the outage in Egypt.

In the example below, Ooredoo (AS8781, formerly Qatar Telecom) lost transit from Lumen (AS3356) and Cogent (AS174) during the outage with inbound traffic shifting to PCCW (AS3491) and Tata (AS6453) in the their absence.

Cloud impacts

As part of our synthetics measurement suite, Kentik measures latency, packet loss and jitter between each of the major public cloud regions. As I mentioned in the opening, even these cloud providers have to rely on the same submarine cable infrastructure that everyone else does. Cloud providers will buy capacity on numerous cables with the objective to maintain connectivity in the event any single cable suffers an outage.

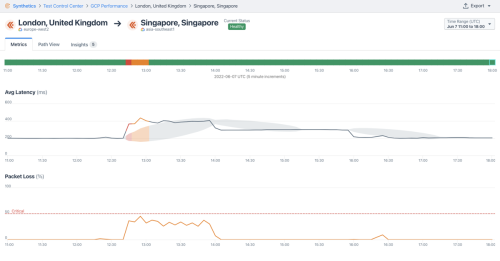

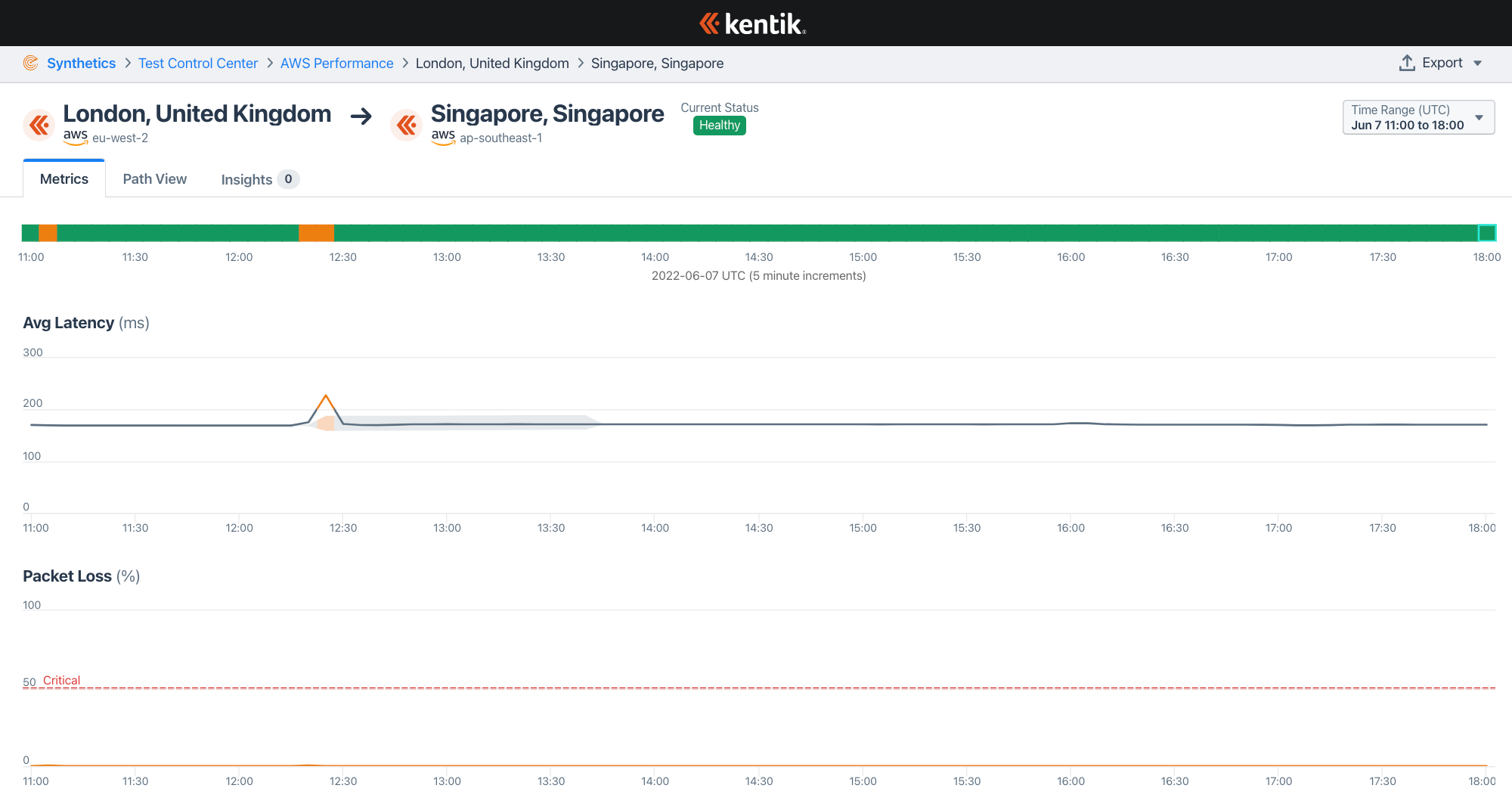

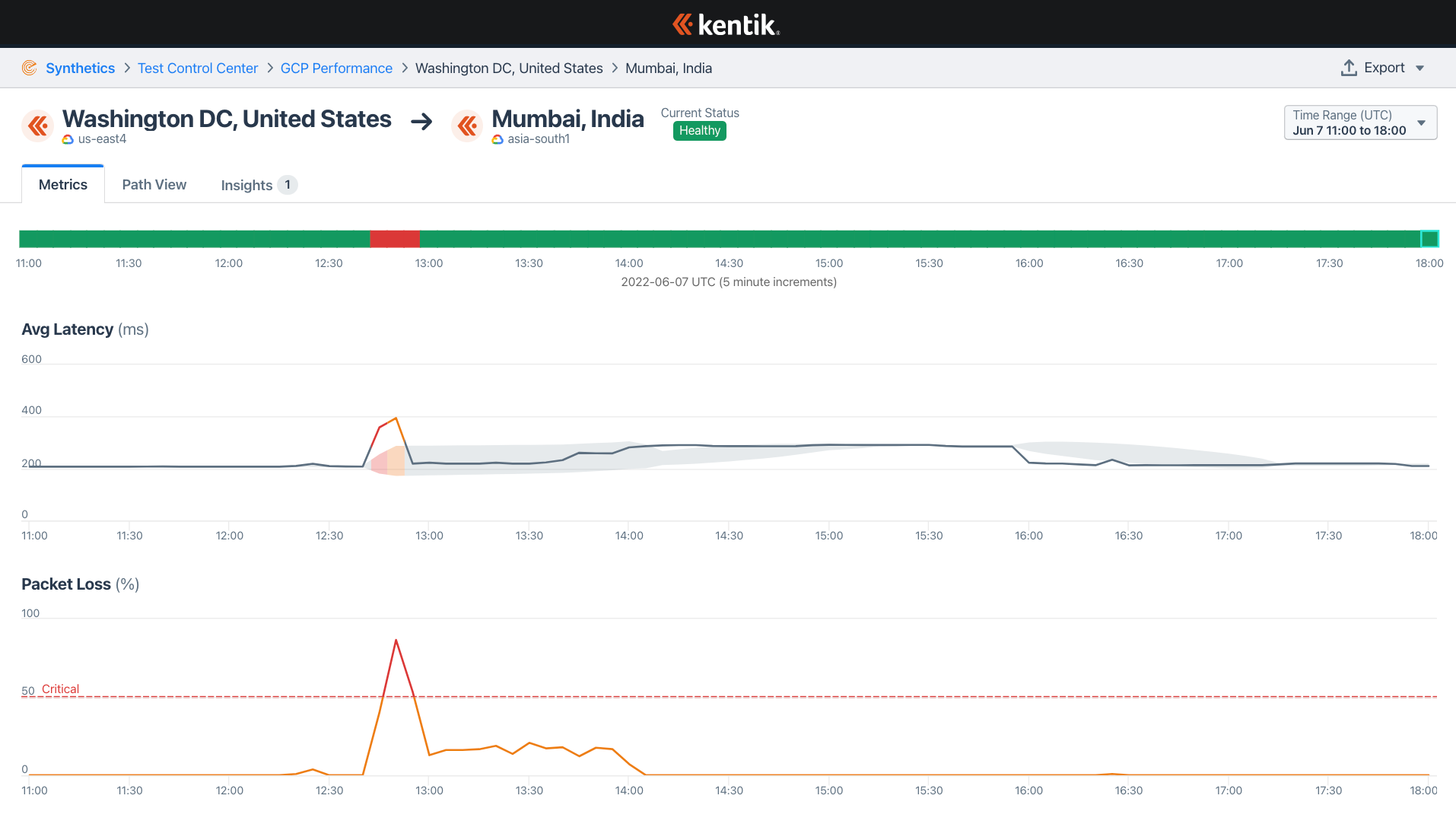

Having said that, it is fascinating to observe the differences between how the major public cloud providers experienced the outage. By choosing routes that are common to AWS, GCP and Azure (London, England to Singapore and Washington DC to Mumbai, India), we can attempt a couple of fair comparisons.

In our data, there appeared to be two distinct outage events at 12:25 and 12:45 UTC. In the charts below, we can see AWS and Azure being briefly impacted at 12:25 UTC, but mostly surviving intact. Conversely, Google’s GCP appears to have felt a far greater impact beginning at 12:45 UTC.

Latencies for AWS returned to normal within minutes after a brief spike. Latencies for Azure remained elevated for hours until returning to previous levels after the outage was resolved. According to our measurements, only GCP experienced large amounts of packet loss for over an hour.

The pattern repeats for other routes as well. Here are three views of measurements from the Washington DC area to Mumbai, India. The greatest impact is visible in GCP, much less in Azure and almost nothing in AWS.

Conclusion

The submarine cable industry continues to try to build alternatives to the Egyptian internet chokepoint. Most recently, Google has teamed up with Telecom Italia Sparkle and Omantel to build the upcoming Blue-Raman cable system. This cable system (depicted in dotted red and orange below) would come ashore in Tel Aviv, Israel before crossing over land to Aqaba, Jordan and continuing on to Mumbai, India.

Global commons are resources that humanity must share like the oceans, the atmosphere and outer space. Whether the internet should be included on that list is a matter of debate, but what is evident is that the global internet depends on shared resources like submarine cables.

This is true whether you are a hyperscale cloud provider or a digital business. In either case, the need for network observability is critical to keeping the packets flowing and delivering services whether the risks are underwater explosives, ship anchors, or sharks!